Shock Level Analysis

Michael Anissimov :: Feb. 2002, updated Jan. 2004

The following is an expansion on transhumanist Eliezer Yudkowsky's "Future Shock

Levels" idea, a rough model that seeks to generalize varying levels of "future

shock" and concepts or technologies characteristically associated with these

distinct levels. The concept of space travel, for example, possesses more

"future shock value" than the concept of air travel, although both are concepts

now familiar to the bulk of 21st century humanity. An example of a statement

likely to incur future shock in the contemporary layperson might be: "barring

any major disasters, there's a strong possibility that medical nanotechnology

will eventually be used to cure all diseases and extend human lifespan

indefinitely". This may be true, it might not be, but if it shocks you, then you

aren't ready to think about the possibility logically. Future shock is a genuine

problem in our world, causing millions to withold support from humanitarian

projects that hinge on a thorough understanding of technological futurism. The

problem of future shock continues to get increasingly serious as technological

progress accelerates; human beings can only absorb so much future shock so fast.

This essay explores the phenomenon of future shock and some possible underlying

causes, then suggests potential solutions and presents a more detailed version

of the Yudkowsky's original scale.

Future Shock

(Although the term "future shock" was originally coined by Alvin Toffler in his

book of the same name in 1970, this essay primarily focuses on Yudkowsky's

extension of that idea into distinct "Future Shock Levels".)

Future shock is defined by Yudkowsky (1999) as being "impressed, frightened, or

blindly enthusiastic" towards the future, or specific social or technological

advances. On the whole, it that those who are more familiar with and sentimental

towards the technological and social states of the past (usually older people or

those who live in rural areas) are, on average, more highly predisposed to being

irrationally frightened than blindly enthusiastic of the future. Conversely, we

should expect those more familiar with and sentimental towards the technological

and social states of the present or future (usually younger people or those who

live in urban areas) are probably more at risk for blind enthusiasm than

irrational fear. From a cursory review of historical responses to new

technologies or social arrangements, it seems that on average, the "irrational

fright" response is significantly more common than the "blind enthusiasm"

response.

It is commonly recognized that the primary distinguishing feature separating the

humans of today from the humans of 50,000 years ago is the sophistication of our

technology. The past 50,000 years have only represented miniscule steps in

mankind's biological evolution. Evolution works on extremely long timescales. It

requires strong selection pressures and tight breeding circles for new,

advantageous mutations to arise and spread. When evolutionary selection

pressures were globally dampened by the forces of reciprocal altruism, better

nutrition, shelter, and medicine, biological evolution massively slowed (from

its already incredibly slow pace!) Factor two: when human breeding circles

expanded from an average size of 100 prospective mates to 1,000 prospective

mates, advantageous mutations began to have more trouble becoming species- or

community-typical, as they tended to be diluted in the ambient static of

quantitative variation among traits that is inherent to larger communities of

organisms.

Biologically, humanity has mostly stayed the same. But ideologically,

memetically, we have progressed. And what is largely responsible for that? Many

would agree that it is our technology. Humanity's ancestral niche was the

African savanna, where we lived in tribes of approximately 200 individuals,

engaged in hunting and gathering exercises year in, year out. The root cause of

the global migration of Homo sapiens, our ability to artificially adapt to and

manipulate the environment, and the formulation of cooperative groups with

significantly more than 200 members was the invention and development of

technology. Without technology, humans would have no particular impetus to

develop substantially varied types of culture, or to formalize the pursuit of

knowledge, or to engage in artistic, philosophical, scientific, or large-scale

humanitarian activities as we know them today. We might have continued on as

unusually intellectual chimpanzees for thousands or even millions of years,

reproducing and dying and suffering without tangible progress of any kind. The

bottom line: evolution is basically over, only ideas and technology change.

Ideas mostly change as a result of technology, although there are subtle

feedback effects at work.

New ideas inevitably emerge with new technologies. Studies have shown that

literate individuals combine and analyze concepts in qualitatively different

ways than illiterate people do (Klawans, 2000). Without the invention of

writing, these concrete neurological differences never would have come into

being. A printing press that allows a middle-class person to directly spread

their ideas to hundreds or thousands of people gives rise to deeply different

memetic dynamics than a society based on word of mouth alone. The possibility of

worldwide travel through cheap aircraft shattered cultural barriers like never

before. The invention of the atomic bomb changed the face of war forever.

Further examples number in the millions or billions. As technology continues to

radically change our world, its singular importance remains undeniable. Although

we tend to delegate most of our attention to the specific attitudes, behaviors,

and thoughts of other humans and depreciate the importance of their inanimate

contexts, it should be remembered that we humans are operating on a richly

structured, largely imbalanced technological playing field worthy of explicit

attention. Oftentimes, the analysis of the underlying technologies enabling

human agents is more pragmatically valuable than specific attention towards the

qualities of the agents themselves.

Humans have a proven history of failure when it comes to predicting future

events, especially events which will influence them personally (Slovic, 2002).

We are much better at predicting trends, which are grounded in past data and may

hold reliably for decades or even centuries. Some trends necessarily culminate

in events. For example, one pervasive trend throughout human history has been an

increased capacity for information exchange between any two individuals. Prior

to the invention of the Internet, this trend was clear. With telephone, fax, and

snail mail operating as the best communication methods of the time, an eventual

advance of some sort was highly probable, and this advance did indeed occur, and

was predicted correctly by thousands of futurists, science fiction writers,

technologists, scientists, and others. Today, it seems astronomically likely

that the maximum possible information flow between any two individuals will

continue to increase (barring any huge disasters), through the mediums of larger

servers, ubiquitous broadband, peer-to-peer networks, free long-distance, and so

on. If no disastrous events intervene, the longer-term future will allow the

actual transfer of cognitive content through advanced nano/neurotechnological

communications media.

Some famous quotes of failed predictions:

"Computers in the future may weigh no more than 1.5 tons." - Popular

Mechanics, 1949

"I think there is a world market for maybe five computers." - Thomas Watson,

chairman of IBM, 1943

"But what... is it good for?" - Engineer at the Advanced Computing Systems

Division of IBM, 1968, commenting on the microchip

"There is no reason anyone would want a computer in their home." - Ken Olson,

president, chairman and founder of Digital Equipment Corp, 1977

"This 'telephone' has too many shortcomings to be seriously considered as a

means of communication. The device is inherently of no value to us."

Western Union internal memo, 1876

"The wireless music box has no imaginable commercial value. Who would pay for

a message sent to nobody in particular?" - David Sarnoff's associates in

response to his urgings for investment in the radio in the 1920s

"The bomb will never go off. I speak as an expert in explosives." - Admiral

William Leahy, US Atomic Bomb Project

"Heavier-than-air flying machines are impossible." - Lord Kelvin, president,

Royal Society, 1895

"Airplanes are interesting toys but of no military value." - Marechal

Ferdinand Foch, Professor of Strategy, Ecole Superieure de Guerre

"Man will never reach the moon regardless of all future scientific advances."

- Dr. Lee De Forest, inventor of the vacuum tube and father of television

"Everything that can be invented has been invented." - Charles H. Duell,

Commissioner, U.S. Office of Patents, 1899

Why are humans so poor at predicting future events, and the invention of future

technologies in particular? Part of the cause goes back to how humans were

originally designed by evolution. Our minds were constructed to solve certain

adaptive challenges, and any mental abilities emerging outside of specific

solutions to these adaptive challenges are probably general-purpose mechanisms

that just happen to be applicable across a broader range of domains than usual

(Cosmides et al, 2001). As a result, humans have few innate mental tools for

analyzing the plausibility or impact events more than a few months distant,

especially phenomena as complex as the arrival of futuristic technologies. We

are not specifically adapted to realistically assessing the likelihood of a

particular technology working successfully or unsuccessfully, or the social

impact of the distribution of that technology. In the ancestral environment, the

environment that humans originally adapted to, new technologies were invented

rarely if at all. The main factor that dictated the fates and fortunes of human

beings would be their short- and medium-term interactions with others. Although

human beings do display a certain degree of logical flexibility, complete

transformation from default human reasoning to a theoretically optimal decision

strategy is not to be expected (Koehler, 2002). Humans have several species-wide

innate mental weaknesses, and a handicap in the area of accurate technological

forecasting is one of them.

Calibration Strategies

Debiasing the negative effects of future shock can be attempted in several ways.

One requires becoming familiar with a wider range of the potential possibilities

the future might offer. Hollywood and television futurism are only of limited

use in this respect; these forms of mass media are customized for the

elicitation of ratings, not scientific accuracy or futurological plausibility.

Higher quality sources would include books and magazines associated with

currents of thought whose past predictions have been confirmed. For example,

less than a decade before the creation of Deep Blue (a chess-playing

supercomputer), chess experts commonly claimed that no computer would make it

past a certain level of expertise in chess. AI experts asserted that these chess

experts were almost certainly wrong. When Deep Blue proved to be an intense

challenge to world chess champion Boris Kasparov, the AI experts' predictions

were confirmed. This is just an isolated example - currents of thought must

build up multiple trials of confirmed predictions before assigning them special

validity is warranted. Conversely, currents of thought which have displayed

multiple failures in prediction should be negatively weighted. This would

strongly depreciate predictions for certain future events; for example, the

emergence of psychic powers or the arrival of extraterrestrials.

Many commentators on the possibility of man-made flying machines prior to the

Wright Brothers were struck by future shock. They observed the performance of

past technology, the mythological history of human flight, and the heavy weight

of proposed airplanes in comparison to birds, and concluded that would-be

aeronauts were simply wasting their time with a physically impossible endeavor.

Interestingly, the physical theory required to appreciate the plausibility of

artificial flight was widely available at the time. Newton's laws of physics can

be used to show why objects heavier than birds are indeed theoretically capable

of flight, and by 2004 been used for exactly this purpose many thousands of

times. This could have been mathematically confirmed by skeptics prior to a

successful flight, but it wasn't. As a result, widespread skepticism of the

possibility of flight persisted until these beliefs were experimentally

disconfirmed. It shouldn't have needed to so that long. "Learning from our

mistakes" in the domain of technological futurism means paying close attention

to theory and closing ourselves off from extraneous factors such as the

surprising-looking comparative weight between proposed airplanes and birds.

The neglect and distrust of scientific models in futurism is not so shocking

considering the neglect of science in general among the public, even among

intellectuals. Direct, personal-level interactions between people are inherently

fascinating to read about, think about, and discuss - the kind of knowledge that

would have helped our ancestors survive on the African savannas. (Struggles for

power within hierarchies, the violation or preservation of social taboos,

displays of personal resources, the phenomenon of romance, etc.) Science

requires explicitly disengaging from these age-old preoccupations and analyzing

phenomonena on more abstract levels. Try turning on the TV or reading a popular

magazine. Soap operas are a distilled-for-TV version of romance, and the evening

news is always heavily politicized. Romance and politics are much more

emotionally engaging than science, technology, futurism, and mathematics, and

require a more modest level of intelligence to understand and participate

within. True scientific futurism is less about exhuastively understanding

traditionally fascinating interactions directly between humans, and more about

understanding the relationship between humans and the technology we create,

including the way that technology modulates everyday human interactions.

However, futurism in popular society is merely a tool to entertain, and popular

society's overall beliefs end up regulating which books, television programs,

messages, and people receive attention. Typical types of human interaction are

as old as our species; they’re largely constant relative to technological

changes. This asymmetric focus on traditional human activity discourages

accurate forecasting of our future. (Perfectly accurate forecasting of the

future is clearly impossible, but if your accuracy rate jumps from, say, 30% to

31%, that small change could translate into thousands of lives or billions of

dollars saved.) The point: calculated rationality and scientific sobriety can be

expected to produce predictions of the future that are actually better than the

guesses of casual laypeople. Not perfect, but consistently better.

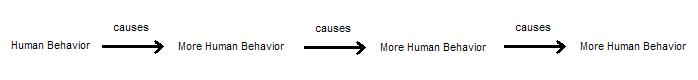

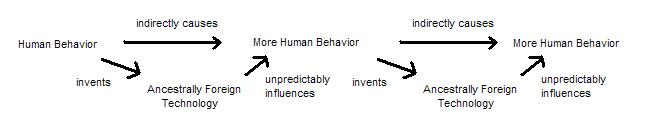

Our human intuitions about societal change come from models that judge how

present-day human behavior might or might not lead to a future state of human

behaviors. In a technological civilization, the changes are not primarily

directed by human behavior changing human behavior, except in the sense of human

engineers creating new technology, which leads to unintuitive future states.

Millions of years of evolution is telling us this is how it works:

When it actually works more like this;

When it actually works more like this;

Discarding the former model for the latter is far more complicated than simply

recognizing it as better. The vast majority of human thinking is automatic;

changing your underlying thinking processes about the future requires

consciously recognizing when you are thinking in human-behavior-causing-human

behavior terms, and this is not easy. Technologies that work reliably - cars,

telephones, houses, and computers - quickly become transparent, integrated into

our usual daily routine. We just forget they're there because they're relatively

seamless. However, this can lead to poor forecasting when we fail to account for

the entire humans + technology meta-system, instead focusing on humans, human

passions, and the salient technologies that just happen to arouse human

passions.

Take the technology of cloning for example. Joe Six-Pack is given the task of

predicting a window of confidence for the technological feasibility and arrival

time for human cloning, in addition to giving a short description of the

sociological effects of the cloning process. Sadly for Joe, the majority of

fictional, popular literature on cloning has involved the immediate creation of

adult copies of a given human being, often gifted with the precise set of

memories the human possesses at the instant of “cloning”. This type of

“cloning”, while technologically extremely difficult (requiring advanced

nanotechnology and molecular scanning procedures rather than simply biotech),

constitutes a “literary attractor” – it’s fun to write and read stories that

conform to it. They sell and people like them. The reason is that the audience

doesn’t know enough science to be sufficiently annoyed to compel large portions

of the population to turn to more accurate sources of fiction. Instant-copy

cloning just seems, intuitively, what cloning should be like. Yet the real

technology of cloning will surely not correspond to Joe's model, and

generalizing from scientifically unrealistic fiction is one of the most

distorting forecasting pathologies of all (Yudkowsky, 2003). Joe's attempts at a

remotely realistic estimate are doomed to fail. We can test the quality of

different futurological "currents of thought" by observing how well their

predictions stand up to the way events in the real world are actually unfolding.

The continuous creation, consumption, and sharing of human media creates a sort

of memetic ecology – an arena where replication and artificial selection takes

place on a grand scale. Imagine a story with ray guns and matter duplicators,

yet a blatant lack of any type of flying machine – be it plane or spaceship.

People would be confused. “How can this civilization have ray guns and matter

duplicators but lack even the simplest propeller plane?” they might say. Such a

story would flounder in the competitive environment of media creation and

distribution, giving way to a more exciting story with ray guns and spaceships

of all sorts included. This artificial selection process will vary in intensity

based on regularities in the annoyance levels and specific interests of the

typical consumer, dictating the shape of clusters in the scientific accuracy of

popular fiction. The most powerful literary attractors currently lie somewhere

in the space between cautious scientific realism and outright nonsense.

(Example: Michael Crichton's "Prey".) These stories often contain odd mixes of

popular, scientifically plausible technologies with popular, scientifically

implausible technologies.

“It’s just a movie!” many people might say to visibly unrealistic science

fiction. But not so to science fiction so profoundly absurd that it rudely

violates the common sense of the audience, loses sales, and quickly passes out

of existence entirely. In fact, most of this type of science fiction is never

created to begin with, because whoever is writing the scripts probably has a

level of technical knowledge about equivalent to the audience, and can empathize

with what they expect and would or would not be annoyed by. This “boundary of

annoyance” creeps forward on a daily basis, as the aggregate population gains

better common sense in the areas of science and technology, what we know about

human nature, and how they interact with one another. The average scientific

accuracy of our “science” fiction slowly creeps upward, but often remains

decades behind what has been obvious to scientifically literate technologists,

futurists and researchers for many years.

The idea of cloning as creating fully-made adult copies of the clonee has not

yet passed into the level of complete and widespread boredom and annoyance. Real

cloning is quite complicated, and requires a knowledge of biology beyond what

most of us learn in high school. Since most people do not continue to read about

biology after graduating high school, they never hit the threshold of annoyance

that reacts to this depiction of cloning. In many areas of the world where

education is even poorer, and religion is ubiquitous, we can hardly expect the

majority of the population to understand even the basic principles of genetics

and evolution. If asked about the likelihood or potential impact of cloning;

they have absolutely nothing to work with. There is no traction to create a

prediction of any sort, and there can never be until the underlying science –

biology, physics, computer science – are studied in sufficient detail. If the

science is absent, traction will eventually be created based on rumors, first

impressions, and the degree to which the proposed technology is representative

of past experiences or thoughts (Citation).

Summary;

Begin forecasting by spending more time carefully examining the various

proposed possibilities.

If any of them shock you, you are not prepared to think logically, and must

desensitize yourself first.

Irrational fear of future advances is relatively more likely than blind

enthusiasm.

The main difference between the past and the present, present and future, is

the technology.

Human nature is relatively constant, but changes slightly based on the

ambient level of technology.

Technology can strongly change human behavior, but humans do not deeply

change technology.

Reliable underlying technology can seem transparent, but it is always

important to take into account.

Be scientific. Read lots of science. Be scientific. Read lots of science. Be

scientific. Read lots of science.

Avoid making generalizations from fiction or science fiction at all costs

(Yudkowsky, 2003a).

The following points are so obvious that it is embarassing to mention them:

Don't fear the future just because it's likely to be different.

Don't underestimate the chance of change because change intimidates you

personally.

Don't love the future just because it's the future.

Don't overestimate the chance of change just because you want it.

Disclaimer: Viewing the following Future Shock Levels as opposing social

factions or exclusive clubs is of course tribalistic, and strongly discouraged.

The Future Shock Levels are not a justificiation for discrimination or

elitism. Just because the really low shock levels sound pretty awful doesn't

mean that the overall scale progresses from "better" to "worse". You're supposed

to make that judgement for yourself.

Now that we've got all the basic futurism out of the way, here are the Shock

Levels!

Discarding the former model for the latter is far more complicated than simply

recognizing it as better. The vast majority of human thinking is automatic;

changing your underlying thinking processes about the future requires

consciously recognizing when you are thinking in human-behavior-causing-human

behavior terms, and this is not easy. Technologies that work reliably - cars,

telephones, houses, and computers - quickly become transparent, integrated into

our usual daily routine. We just forget they're there because they're relatively

seamless. However, this can lead to poor forecasting when we fail to account for

the entire humans + technology meta-system, instead focusing on humans, human

passions, and the salient technologies that just happen to arouse human

passions.

Take the technology of cloning for example. Joe Six-Pack is given the task of

predicting a window of confidence for the technological feasibility and arrival

time for human cloning, in addition to giving a short description of the

sociological effects of the cloning process. Sadly for Joe, the majority of

fictional, popular literature on cloning has involved the immediate creation of

adult copies of a given human being, often gifted with the precise set of

memories the human possesses at the instant of “cloning”. This type of

“cloning”, while technologically extremely difficult (requiring advanced

nanotechnology and molecular scanning procedures rather than simply biotech),

constitutes a “literary attractor” – it’s fun to write and read stories that

conform to it. They sell and people like them. The reason is that the audience

doesn’t know enough science to be sufficiently annoyed to compel large portions

of the population to turn to more accurate sources of fiction. Instant-copy

cloning just seems, intuitively, what cloning should be like. Yet the real

technology of cloning will surely not correspond to Joe's model, and

generalizing from scientifically unrealistic fiction is one of the most

distorting forecasting pathologies of all (Yudkowsky, 2003). Joe's attempts at a

remotely realistic estimate are doomed to fail. We can test the quality of

different futurological "currents of thought" by observing how well their

predictions stand up to the way events in the real world are actually unfolding.

The continuous creation, consumption, and sharing of human media creates a sort

of memetic ecology – an arena where replication and artificial selection takes

place on a grand scale. Imagine a story with ray guns and matter duplicators,

yet a blatant lack of any type of flying machine – be it plane or spaceship.

People would be confused. “How can this civilization have ray guns and matter

duplicators but lack even the simplest propeller plane?” they might say. Such a

story would flounder in the competitive environment of media creation and

distribution, giving way to a more exciting story with ray guns and spaceships

of all sorts included. This artificial selection process will vary in intensity

based on regularities in the annoyance levels and specific interests of the

typical consumer, dictating the shape of clusters in the scientific accuracy of

popular fiction. The most powerful literary attractors currently lie somewhere

in the space between cautious scientific realism and outright nonsense.

(Example: Michael Crichton's "Prey".) These stories often contain odd mixes of

popular, scientifically plausible technologies with popular, scientifically

implausible technologies.

“It’s just a movie!” many people might say to visibly unrealistic science

fiction. But not so to science fiction so profoundly absurd that it rudely

violates the common sense of the audience, loses sales, and quickly passes out

of existence entirely. In fact, most of this type of science fiction is never

created to begin with, because whoever is writing the scripts probably has a

level of technical knowledge about equivalent to the audience, and can empathize

with what they expect and would or would not be annoyed by. This “boundary of

annoyance” creeps forward on a daily basis, as the aggregate population gains

better common sense in the areas of science and technology, what we know about

human nature, and how they interact with one another. The average scientific

accuracy of our “science” fiction slowly creeps upward, but often remains

decades behind what has been obvious to scientifically literate technologists,

futurists and researchers for many years.

The idea of cloning as creating fully-made adult copies of the clonee has not

yet passed into the level of complete and widespread boredom and annoyance. Real

cloning is quite complicated, and requires a knowledge of biology beyond what

most of us learn in high school. Since most people do not continue to read about

biology after graduating high school, they never hit the threshold of annoyance

that reacts to this depiction of cloning. In many areas of the world where

education is even poorer, and religion is ubiquitous, we can hardly expect the

majority of the population to understand even the basic principles of genetics

and evolution. If asked about the likelihood or potential impact of cloning;

they have absolutely nothing to work with. There is no traction to create a

prediction of any sort, and there can never be until the underlying science –

biology, physics, computer science – are studied in sufficient detail. If the

science is absent, traction will eventually be created based on rumors, first

impressions, and the degree to which the proposed technology is representative

of past experiences or thoughts (Citation).

Summary;

Begin forecasting by spending more time carefully examining the various

proposed possibilities.

If any of them shock you, you are not prepared to think logically, and must

desensitize yourself first.

Irrational fear of future advances is relatively more likely than blind

enthusiasm.

The main difference between the past and the present, present and future, is

the technology.

Human nature is relatively constant, but changes slightly based on the

ambient level of technology.

Technology can strongly change human behavior, but humans do not deeply

change technology.

Reliable underlying technology can seem transparent, but it is always

important to take into account.

Be scientific. Read lots of science. Be scientific. Read lots of science. Be

scientific. Read lots of science.

Avoid making generalizations from fiction or science fiction at all costs

(Yudkowsky, 2003a).

The following points are so obvious that it is embarassing to mention them:

Don't fear the future just because it's likely to be different.

Don't underestimate the chance of change because change intimidates you

personally.

Don't love the future just because it's the future.

Don't overestimate the chance of change just because you want it.

Disclaimer: Viewing the following Future Shock Levels as opposing social

factions or exclusive clubs is of course tribalistic, and strongly discouraged.

The Future Shock Levels are not a justificiation for discrimination or

elitism. Just because the really low shock levels sound pretty awful doesn't

mean that the overall scale progresses from "better" to "worse". You're supposed

to make that judgement for yourself.

Now that we've got all the basic futurism out of the way, here are the Shock

Levels!

Future Shock Levels

SL-2 (negative two):

Hardcore Neo-Luddites (anti-technologists), primitive tribal societies, the

Amish. This future shock level represents familarity and comfort with the

technology of a century or two ago, and not much more. Due to a lack of

communication technology, information sources are limited to a few hundred

people, likely possessing very similar worldviews. These conditions can

precipitate the emergence and festering of false or destructive memes

(citation). Daily life is often accompanied by a large amount of difficult,

repetitive work and few real returns for the work done. SL-2s may avoid

medical assistance or unfamiliar foods even if their lives are at risk. The

vast majority SL-2s will be illiterate. I estimate 500 million or so SL-2s

worldwide, with millions thankfully moving to SL-1 or SL0 per year.

SL-1 (negative one):

A decent percentage of people who live in poor rural areas or Third World

countries. Barely exposed to modern technology, WWII-era technology is

likely to be prevalent. Automobiles, engines, radios, and so on may be the

forefront of available technology. Since some of these technologies must be

purchased in areas heavily populated by those at higher future shock levels,

some exposure is inevitable, and many SL-1s worldwide are rapidly becoming

SL0. (Especially anyone in the younger generations.) These individuals would

probably have extreme difficulty imagining what an "Internet" would be like

without an elaborate and extended explanation. SL-1s are distinct from SL0s

in that they would be "shocked" by SL1 and downright confused or scared of

SL2 and above.

Sadly, due to communication technology limitations and poor education, these

folks will probably have a fundamentalist bent, either religiously or

ideologically. There is a good chance they will be apprehensive towards or

entirely unaware of modern day technology such as computers and other modern

era tools. Since all the technology they are familiar with is relatively

crude, simple, and slightly dehumanizing, the prospect of using large amounts

of technology to radically improve life may sound implausible under any

circumstances. Many concepts are in easy-to-understand black and whites, no

continuities or "fuzzy thinking". Natural and artificial are entirely

different and seperate. So are "science" and religion. God and Man. And so

on. A good chunk of SL-1s will be illiterate and many will not progress

beyond the equivalent of a low high school education. This isn't their fault,

and it doesn't make them bad people. SL-1s make up the majority of the

species; maybe somewhere around 3.5 billion people. As mentioned before, SL

1s have steadily been adopting SL0 ideologies and lifestyles en masse since

WWII, with very few reverting to SL-2.

SL0:

The “legendary normal person”, as Yudkowsky puts it. Original description

reads, "The legendary average person is comfortable with modern technology

not so much the frontiers of modern technology, but the technology used in

everyday life. Most people, TV anchors, journalists, politicians." These

folks may have access to the Internet and assorted gadgets around the house,

like a modern TV set, digital clock, automatic shaver, or whatever. Quite

often possesses the hard dichotomous view of technology and humanity which

makes it drastically difficult to step up to Shock Level 1 or Shock Level 2

ideas. Daily conversation may indeed bring up technology a fair portion of

the time; bearing in mind technology has already saturated most of the

affluent world. Technological improvements will generally be viewed as

incremental improvements in efficiency or entertainment, but rarely as

revolutionary or world-changing. An ambient distrust of technology may be

accompanied by a notion that the broad outlines of technological progress are

manipulable to human agencies (including the ability to "pull the plug"),

when in fact they are not.

These individuals generally assume that the lives of the people in each

successive generation will be essentially the same as their previous

generation, with a slight improvement in science and technology and a minor

increase in lifespan and quality of life. Untraditional technological

advances may be approached with distrust or suspicion, manifesting itself in

the "Precautionary Principle", which demands that researchers convince major

portions of the population to eplicitly advocate the development of their

chosen technology. As the pace of progress continues to visibly accelerate,

many will polarize to technophilic and technophobic ends of the belief

spectrum. But for now, they primarily believe what they see on TV or

newspapers (an odd mix of technophilic and technophobic memes apparently

distinct to our time period). Seems to be the default level for most of

First World civilization. Jetsons-esque visions of the future. Maybe 2

billion folks or so, with tens or hundreds of thousands per year migrating to

SL1, and very few moving to SL-1. Seems like a strong, large, and stable

memetic attractor.

SL1:

The typical forward-thinking person. The original scale describes SL1 as

"Virtual reality, living to be a hundred, "The Road Ahead", "To Renew

America", "Future Shock", the frontiers of modern technology as seen by Wired

magazine. Scientists, novelty-seekers, early-adopters, programmers,

technophiles." SL1s are hose who stay relatively current with technology. As

stated in the original description, this level overlaps strongly with the

portion of society containing researchers, programmers, tech investors,

internet roleplayers, technology enthusiasts, and other science-and

technology-minded people. It seems that if a "normal" person is exposed to

enough technology and realistic futurism in the right way, they will

eventually become SL1s. Relatively conservative extrapolations of future

progress in computing, robotics, the Internet, and biotechnology are

represented here. Extension of average lifespan to 100 or so, robot maids,

and the like. May entertain ideas of aliens, interplanetary colonies,

antimatter rockets, and so on (not in an exclusively fictional sense). Every

time a space mission or surprising technological advance is widely covered on

the news, a few ten or hundred thousand SL1s will pop into existence.

SL1s may point out physically unrealistic or scientifically implausible

aspects of science fiction stories. They probably prefer speculation and

discussion of the future of mankind to thoughts of an afterlife.

Anthropomorphic models of future artificial intelligences and transhumans

will be inevitable, if such models exist at all. The "linear intuitive"

vision of the future is more likely to be held than the historically

realistic exponential view. SL1s will probably be well-educated, relatively

bibliophilic and intellectual, and most likely young or middle aged (but not

always!) SL1s are probably not incredibly rare; we can estimate at least 10

million worldwide. (Roughly one six-hundreth of the world population, or

about one two-hundreth the population of affluent countries.) Tens or even

hundreds of thousands of SL1ers will reach SL2 per year, many of them youth

who grew up with SL1 parents and peers.

SL2:

The average science fiction fan. Yudkowsky's original description reads

"Medical immortality, interplanetary exploration, major genetic engineering,

and new ("alien") cultures." A common pasttime of this group might be

speculation and discussion of extraterrestrial civilizations and highly

advanced technology such as superlasers, starships, swarms of nanobots,

human-equivalent (but rarely transhuman) AIs, and major bodily augmentation.

Realization of additional implications of biotechnology (clinical immortality

and genetic engineering), computing (ubiquitous computing, 3D displays),

robotics (elimination of manual labor) are inevitable. The idea of extreme

plentitude and the potential elimination of poverty and illness might come

into play. Starships, antimatter, cloaking; like many other future shock

levels, this one features an unusual mix of physically realistic and

physically unrealistic technologies. Many people who are casually interested

in nanotechnology would probably fall into SL2, as would many life

extensionists.

As their futurological models develop, SL2s may quickly find themselves

unsatisfied with mainstream futurism and science fiction. Major

technological advancements don't seem as far away to this person than to

most, possibly due to an adoption of the historically realistic exponential

model of progress as opposed to an intuitive linear model. Anthropomorphism,

the hard distinctions between artificial and natural, matter and software,

virtual and real, human and non-human, begin to slowly fade. Physicist Michio

Kaku would be a typical example of futurist thinking in line with the SL2

platform. Many SL2s hold informal transhumanist philosophies. Perhaps one

million or more individuals, each potentially receptive to SL3 or SL4 memes.

Somewhere between a thousand and fifty thousand SL2s proceed to SL3 every

year, with a slightly smaller number migrating to SL1 and dismissing SL2

concepts as pie-in-the-sky and largely irrelevant to our current condition.

SL3:

Serious transhumanists. Original description reads, "nanotechnology, human

equivalent AI, minor intelligence enhancement, uploading, total body

revision, intergalactic exploration", although it seems appropriate to think

of nanotechnology, human-equivalent AI, and intergalactic exploration as SL2

concepts, because they are actually quite common and mainstream nowadays, and

familiarity with these concepts does not denote what is usually meant by

"SL3". SL3 represents a highly relevant and interesting threshold.

Transhumanists seek to improve their mental, emotional, and physical

capacities by changing the physical structure of our bodies and brains. For

better or for worse, SL3 contains the real mind blowing stuff. Sophisticated

nanotechnology, total body/mind revision through nanomedicine, uploading,

potential posthumanity, Von Neumann probes, intergalactic travel, expansion

throughout the universe, Dyson spheres, and the faint beginnings of

nonanthropomorphic portrayals of AIs and other nonhuman intelligences are all

common. SL3s tend to be scientifically rigorous and heavily bibliophilic.

Thoughts regarding SL3-level concepts may be prompted by readings in fiction

or non-fiction, although the latter is significantly more common.

Most transhumanists want to live forever under the best possible conditions,

expanding their bodies and minds, essentially becoming godlike by today's

standards. They want to engineer out negative emotions and enhance their own

intelligence. SL3s probably realize that intelligence is potentially

hardware-extensible, and look forward to enhancing and expanding the physical

substrate underlying their minds. SL3s often display an interest in memetics,

advanced evolutionary thinking, and cutting-edge philosophy of science. Well

known science fiction authors discussing SL3 concepts would include Greg

Egan, Vernor Vinge, Damien Broderick, and John Wright. Well-known non-fiction

authors discussing SL3 concepts include Hans Moravec, Ray Kurzweil, Ed Regis,

Hugo de Garis, and Bart Kosko. The popular BetterHumans website features many

interesting stories on SL3 and SL2 concepts. The boundaries between SL2 and

SL3 can be fuzzy at times, but it seems safe to say that there are probably

between 1,000 and 100,000 SL3s in existence, with between 1,000 and 10,000

moving back to SL2 every year, and between 5 and 20 migrating to SL4.

SL4:

Singularity advocates and analysts. (And possibly DARPA strategists studying

nano-bio-info-cogno convergence; who knows?) Sysop Scenario, singletons, deep

thought about the implications of uploading and virtual realities, Jupiter

Brains, Apotheosis, Alpha-point computing, evaporation of the human ontology,

complete mental revision, recursively self-improving artificial intelligence,

that sort of stuff. Many SL4s are interested in artificial general

intelligence (Yudkowsky, 2003b). SL4s interested in SL4 concepts generally

require a strong scientific background to understand these ideas and

communicate them to others (this alone doesn't necessarily say anything about

their validity, but it remains a fact). Fiction authors John Wright and

Vernor Vinge are probably borderline SL4. Non-fiction writers Eliezer

Yudkowsky, Nick Bostrom, and myself are all SL4. There are somewhere between

20 and 100 SL4ers out there, depending on what you call "SL4". "Staring Into

the Singularity" is probably the first and most intense of SL4 writings

online. SL4 ideas and people are apparently so eccentric and unusual that the

San Francisco Chronicle, Wired, and Slashdot have all bothered to take the

time to make fun of them. SL4s ideas can shock SL2s and even SL3s. SL4s

believe that the creation of qualitatively smarter-than-human intelligence

could result in discontinuous levels of progress. The comparative value of

various SL4 concepts has been an intense topic of debate among transhumanist

communities for almost half a decade now, and this will probably continue to

be the case indefinitely.

Bibliography:

Bostrom, Nick. (2003). "Ethical Issues in Advanced Artificial Intelligence".

Cognitive, Emotive and Ethical Aspects of Decision Making in Humans and in

Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 2, ed. I. Smit et al., Int. Institute of Advanced

Studies in Systems Research and Cybernetics, 2003, pp. 12-17.

http://www.nickbostrom.com/ethics/ai.html

Cosmides, L., Tooby, J. (2001.) Evolutionary Psychology Primer. Webpage.

http://www.psych.ucsb.edu/research/cep/primer.html

McKie, Robin. (2002.) Is human evolution finally over? The Observer

International. http://observer.guardian.co.uk/

Slovic, P., Finucane, M., Peters, E., MacGregor, D. (2002.) When Predictions

Fail: The Dilemma of Unrealistic Optimism. In Heuristics and Biases (pp. 335

347), T. Gilovich, D. Griffin, D. Kahneman (Eds.). Cambridge, U.K: Cambridge

University Press.

Smart, John. (2001.) What is the Singularity? http://singularitywatch.com

Koehler, D., Brenner, L., Griffin, D. (2002.) The Calibration of Expert

Judgement: Heuristics and Biases Beyond the Laboratory. In Heuristics and Biases

(pp. 6-420), T. Gilovich, D. Griffin, D. Kahneman (Eds.). Cambridge, U.K:

Cambridge University Press.

Klawans, Harold. (2003). Strange Behavior: Tales of Evolutionary Neurology. New

York: W.W. Norton and Co.

Yudkowsky, Eliezer. (1999). "Future Shock Levels". Webpage.

http://www.yudkowsky.net/shocklevels.html

Yudkowsky, Eliezer. (2003a). "Predicting the Future". Talk given at the World

Futures Symposium 2003, sponsored by the New York Transhumanist Association.

http://www.sl4.org/bin/wiki.pl?PredictingTheFuture

Yudkowsky, Eliezer. (2003b). "Levels of Organization in General Intelligence".

Publication of the Singularity Institute: http://singinst.org/LOGI/ To appear in

Advances in Artificial General Intelligence, Goertzel and Pennachin, eds.

When it actually works more like this;

When it actually works more like this;

Discarding the former model for the latter is far more complicated than simply

recognizing it as better. The vast majority of human thinking is automatic;

changing your underlying thinking processes about the future requires

consciously recognizing when you are thinking in human-behavior-causing-human

behavior terms, and this is not easy. Technologies that work reliably - cars,

telephones, houses, and computers - quickly become transparent, integrated into

our usual daily routine. We just forget they're there because they're relatively

seamless. However, this can lead to poor forecasting when we fail to account for

the entire humans + technology meta-system, instead focusing on humans, human

passions, and the salient technologies that just happen to arouse human

passions.

Take the technology of cloning for example. Joe Six-Pack is given the task of

predicting a window of confidence for the technological feasibility and arrival

time for human cloning, in addition to giving a short description of the

sociological effects of the cloning process. Sadly for Joe, the majority of

fictional, popular literature on cloning has involved the immediate creation of

adult copies of a given human being, often gifted with the precise set of

memories the human possesses at the instant of “cloning”. This type of

“cloning”, while technologically extremely difficult (requiring advanced

nanotechnology and molecular scanning procedures rather than simply biotech),

constitutes a “literary attractor” – it’s fun to write and read stories that

conform to it. They sell and people like them. The reason is that the audience

doesn’t know enough science to be sufficiently annoyed to compel large portions

of the population to turn to more accurate sources of fiction. Instant-copy

cloning just seems, intuitively, what cloning should be like. Yet the real

technology of cloning will surely not correspond to Joe's model, and

generalizing from scientifically unrealistic fiction is one of the most

distorting forecasting pathologies of all (Yudkowsky, 2003). Joe's attempts at a

remotely realistic estimate are doomed to fail. We can test the quality of

different futurological "currents of thought" by observing how well their

predictions stand up to the way events in the real world are actually unfolding.

The continuous creation, consumption, and sharing of human media creates a sort

of memetic ecology – an arena where replication and artificial selection takes

place on a grand scale. Imagine a story with ray guns and matter duplicators,

yet a blatant lack of any type of flying machine – be it plane or spaceship.

People would be confused. “How can this civilization have ray guns and matter

duplicators but lack even the simplest propeller plane?” they might say. Such a

story would flounder in the competitive environment of media creation and

distribution, giving way to a more exciting story with ray guns and spaceships

of all sorts included. This artificial selection process will vary in intensity

based on regularities in the annoyance levels and specific interests of the

typical consumer, dictating the shape of clusters in the scientific accuracy of

popular fiction. The most powerful literary attractors currently lie somewhere

in the space between cautious scientific realism and outright nonsense.

(Example: Michael Crichton's "Prey".) These stories often contain odd mixes of

popular, scientifically plausible technologies with popular, scientifically

implausible technologies.

“It’s just a movie!” many people might say to visibly unrealistic science

fiction. But not so to science fiction so profoundly absurd that it rudely

violates the common sense of the audience, loses sales, and quickly passes out

of existence entirely. In fact, most of this type of science fiction is never

created to begin with, because whoever is writing the scripts probably has a

level of technical knowledge about equivalent to the audience, and can empathize

with what they expect and would or would not be annoyed by. This “boundary of

annoyance” creeps forward on a daily basis, as the aggregate population gains

better common sense in the areas of science and technology, what we know about

human nature, and how they interact with one another. The average scientific

accuracy of our “science” fiction slowly creeps upward, but often remains

decades behind what has been obvious to scientifically literate technologists,

futurists and researchers for many years.

The idea of cloning as creating fully-made adult copies of the clonee has not

yet passed into the level of complete and widespread boredom and annoyance. Real

cloning is quite complicated, and requires a knowledge of biology beyond what

most of us learn in high school. Since most people do not continue to read about

biology after graduating high school, they never hit the threshold of annoyance

that reacts to this depiction of cloning. In many areas of the world where

education is even poorer, and religion is ubiquitous, we can hardly expect the

majority of the population to understand even the basic principles of genetics

and evolution. If asked about the likelihood or potential impact of cloning;

they have absolutely nothing to work with. There is no traction to create a

prediction of any sort, and there can never be until the underlying science –

biology, physics, computer science – are studied in sufficient detail. If the

science is absent, traction will eventually be created based on rumors, first

impressions, and the degree to which the proposed technology is representative

of past experiences or thoughts (Citation).

Summary;

Begin forecasting by spending more time carefully examining the various

proposed possibilities.

If any of them shock you, you are not prepared to think logically, and must

desensitize yourself first.

Irrational fear of future advances is relatively more likely than blind

enthusiasm.

The main difference between the past and the present, present and future, is

the technology.

Human nature is relatively constant, but changes slightly based on the

ambient level of technology.

Technology can strongly change human behavior, but humans do not deeply

change technology.

Reliable underlying technology can seem transparent, but it is always

important to take into account.

Be scientific. Read lots of science. Be scientific. Read lots of science. Be

scientific. Read lots of science.

Avoid making generalizations from fiction or science fiction at all costs

(Yudkowsky, 2003a).

The following points are so obvious that it is embarassing to mention them:

Don't fear the future just because it's likely to be different.

Don't underestimate the chance of change because change intimidates you

personally.

Don't love the future just because it's the future.

Don't overestimate the chance of change just because you want it.

Disclaimer: Viewing the following Future Shock Levels as opposing social

factions or exclusive clubs is of course tribalistic, and strongly discouraged.

The Future Shock Levels are not a justificiation for discrimination or

elitism. Just because the really low shock levels sound pretty awful doesn't

mean that the overall scale progresses from "better" to "worse". You're supposed

to make that judgement for yourself.

Now that we've got all the basic futurism out of the way, here are the Shock

Levels!

Discarding the former model for the latter is far more complicated than simply

recognizing it as better. The vast majority of human thinking is automatic;

changing your underlying thinking processes about the future requires

consciously recognizing when you are thinking in human-behavior-causing-human

behavior terms, and this is not easy. Technologies that work reliably - cars,

telephones, houses, and computers - quickly become transparent, integrated into

our usual daily routine. We just forget they're there because they're relatively

seamless. However, this can lead to poor forecasting when we fail to account for

the entire humans + technology meta-system, instead focusing on humans, human

passions, and the salient technologies that just happen to arouse human

passions.

Take the technology of cloning for example. Joe Six-Pack is given the task of

predicting a window of confidence for the technological feasibility and arrival

time for human cloning, in addition to giving a short description of the

sociological effects of the cloning process. Sadly for Joe, the majority of

fictional, popular literature on cloning has involved the immediate creation of

adult copies of a given human being, often gifted with the precise set of

memories the human possesses at the instant of “cloning”. This type of

“cloning”, while technologically extremely difficult (requiring advanced

nanotechnology and molecular scanning procedures rather than simply biotech),

constitutes a “literary attractor” – it’s fun to write and read stories that

conform to it. They sell and people like them. The reason is that the audience

doesn’t know enough science to be sufficiently annoyed to compel large portions

of the population to turn to more accurate sources of fiction. Instant-copy

cloning just seems, intuitively, what cloning should be like. Yet the real

technology of cloning will surely not correspond to Joe's model, and

generalizing from scientifically unrealistic fiction is one of the most

distorting forecasting pathologies of all (Yudkowsky, 2003). Joe's attempts at a

remotely realistic estimate are doomed to fail. We can test the quality of

different futurological "currents of thought" by observing how well their

predictions stand up to the way events in the real world are actually unfolding.

The continuous creation, consumption, and sharing of human media creates a sort

of memetic ecology – an arena where replication and artificial selection takes

place on a grand scale. Imagine a story with ray guns and matter duplicators,

yet a blatant lack of any type of flying machine – be it plane or spaceship.

People would be confused. “How can this civilization have ray guns and matter

duplicators but lack even the simplest propeller plane?” they might say. Such a

story would flounder in the competitive environment of media creation and

distribution, giving way to a more exciting story with ray guns and spaceships

of all sorts included. This artificial selection process will vary in intensity

based on regularities in the annoyance levels and specific interests of the

typical consumer, dictating the shape of clusters in the scientific accuracy of

popular fiction. The most powerful literary attractors currently lie somewhere

in the space between cautious scientific realism and outright nonsense.

(Example: Michael Crichton's "Prey".) These stories often contain odd mixes of

popular, scientifically plausible technologies with popular, scientifically

implausible technologies.

“It’s just a movie!” many people might say to visibly unrealistic science

fiction. But not so to science fiction so profoundly absurd that it rudely

violates the common sense of the audience, loses sales, and quickly passes out

of existence entirely. In fact, most of this type of science fiction is never

created to begin with, because whoever is writing the scripts probably has a

level of technical knowledge about equivalent to the audience, and can empathize

with what they expect and would or would not be annoyed by. This “boundary of

annoyance” creeps forward on a daily basis, as the aggregate population gains

better common sense in the areas of science and technology, what we know about

human nature, and how they interact with one another. The average scientific

accuracy of our “science” fiction slowly creeps upward, but often remains

decades behind what has been obvious to scientifically literate technologists,

futurists and researchers for many years.

The idea of cloning as creating fully-made adult copies of the clonee has not

yet passed into the level of complete and widespread boredom and annoyance. Real

cloning is quite complicated, and requires a knowledge of biology beyond what

most of us learn in high school. Since most people do not continue to read about

biology after graduating high school, they never hit the threshold of annoyance

that reacts to this depiction of cloning. In many areas of the world where

education is even poorer, and religion is ubiquitous, we can hardly expect the

majority of the population to understand even the basic principles of genetics

and evolution. If asked about the likelihood or potential impact of cloning;

they have absolutely nothing to work with. There is no traction to create a

prediction of any sort, and there can never be until the underlying science –

biology, physics, computer science – are studied in sufficient detail. If the

science is absent, traction will eventually be created based on rumors, first

impressions, and the degree to which the proposed technology is representative

of past experiences or thoughts (Citation).

Summary;

Begin forecasting by spending more time carefully examining the various

proposed possibilities.

If any of them shock you, you are not prepared to think logically, and must

desensitize yourself first.

Irrational fear of future advances is relatively more likely than blind

enthusiasm.

The main difference between the past and the present, present and future, is

the technology.

Human nature is relatively constant, but changes slightly based on the

ambient level of technology.

Technology can strongly change human behavior, but humans do not deeply

change technology.

Reliable underlying technology can seem transparent, but it is always

important to take into account.

Be scientific. Read lots of science. Be scientific. Read lots of science. Be

scientific. Read lots of science.

Avoid making generalizations from fiction or science fiction at all costs

(Yudkowsky, 2003a).

The following points are so obvious that it is embarassing to mention them:

Don't fear the future just because it's likely to be different.

Don't underestimate the chance of change because change intimidates you

personally.

Don't love the future just because it's the future.

Don't overestimate the chance of change just because you want it.

Disclaimer: Viewing the following Future Shock Levels as opposing social

factions or exclusive clubs is of course tribalistic, and strongly discouraged.

The Future Shock Levels are not a justificiation for discrimination or

elitism. Just because the really low shock levels sound pretty awful doesn't

mean that the overall scale progresses from "better" to "worse". You're supposed

to make that judgement for yourself.

Now that we've got all the basic futurism out of the way, here are the Shock

Levels!